Xmpp-Server

XMPP Servers

An XMPP server provides basic messaging, presence, and XML routing features. This page lists Jabber/XMPP server software that you can use to run your own XMPP service, either over the Internet or on a local area network.

Note: The following software was not developed by the XMPP Standards Foundation and has not been formally tested for standards compliance, usability, reliability, or performance.

See something missing? Any list of XMPP servers, clients or libraries will, due to the dynamic and evolving nature of the XMPP market, be out of date almost as soon as it’s published. If you are related to the project and spot mistakes, errors or omissions in the table below, please submit a pull request!

Project Name

Platforms

AstraChat

Linux / macOS / Solaris / Windows

ejabberd

Linux / macOS / Windows

Isode M-Link

Linux / Windows

jackal

Linux / macOS

Metronome IM

Linux

MongooseIM

Openfire

Prosody IM

BSD / Linux / macOS

An Overview of XMPP

XMPP is the Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol, a set of open technologies for instant messaging, presence, multi-party chat, voice and video calls, collaboration, lightweight middleware, content syndication, and generalized routing of XML data.

XMPP was originally developed in the Jabber open-source community to provide an open, decentralized alternative to the closed instant messaging services at that time. XMPP offers several key advantages over such services:

Open — the XMPP protocols are free, open, public, and easily understandable; in addition, multiple implementations exist in the form of clients, servers, server components, and code libraries.

Standard — the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) has formalized the core XML streaming protocols as an approved instant messaging and presence technology. The XMPP specifications were published as RFC 3920 and RFC 3921 in 2004, and the XMPP Standards Foundation continues to publish many XMPP Extension Protocols. In 2011 the core RFCs were revised, resulting in the most up-to-date specifications (RFC 6120, RFC 6121, and RFC 7622).

Proven — the first Jabber/XMPP technologies were developed by Jeremie Miller in 1998 and are now quite stable; hundreds of developers are working on these technologies, there are tens of thousands of XMPP servers running on the Internet today, and millions of people use XMPP for instant messaging through public services such as Google Talk and XMPP deployments at organizations worldwide.

Decentralized — the architecture of the XMPP network is similar to email; as a result, anyone can run their own XMPP server, enabling individuals and organizations to take control of their communications experience.

Secure — any XMPP server may be isolated from the public network (e. g., on a company intranet) and robust security using SASL and TLS has been built into the core XMPP specifications. In addition, the XMPP developer community is actively working on end-to-end encryption to raise the security bar even further.

Extensible — using the power of XML, anyone can build custom functionality on top of the core protocols; to maintain interoperability, common extensions are published in the XEP series, but such publication is not required and organizations can maintain their own private extensions if so desired.

Flexible — XMPP applications beyond IM include network management, content syndication, collaboration tools, file sharing, gaming, remote systems monitoring, web services, lightweight middleware, cloud computing, and much more.

Diverse — a wide range of companies and open-source projects use XMPP to build and deploy real-time applications and services; you will never get “locked in” when you use XMPP technologies.

This page provides an introduction to various XMPP technologies, including links to specifications, implementations, tutorials, and special-purpose discussion venues.

Key XMPP technologies:

Core — information about the core XMPP technologies for XML streaming

Jingle — SIP-compatible multimedia signalling for voice, video, file transfer, and other applications

Multi-User Chat — flexible, multi-party communication

PubSub — alerts and notifications for data syndication, rich presence, and more

BOSH — an HTTP binding for XMPP (and other) traffic

Core

At its core, XMPP is a technology for streaming XML over a network. The protocol, which emerged from the Jabber open-source community in 1999, was originally designed to provide an open, secure, decentralized alternative to consumer-oriented instant messaging (IM) services like ICQ, AIM, and MSN. The core technologies were formalized under the name Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP) at the IETF in 2004. These core technologies include:

The base XML streaming layer

Channel encryption using Transport Layer Security (TLS)

Strong authentication using the Simple Authentication and Security Layer (SASL)

Use of UTF-8 for complete Unicode support, including fully internationalized addresses

Built-in information about network availability (“presence”)

Presence subscriptions for two-way authorization

Presence-enabled contact lists (“rosters”)

Specifications

The core XMPP technologies are defined in two RFCs published by the IETF:

RFC 6120: XMPP Core

RFC 6121: XMPP IM

RFC 7622: XMPP Address Format

The first XMPP RFCs (RFC 3920 and RFC 3921) were produced by the IETF’s XMPP Working Group in October 2004. In 2011 they were revised, resulting in the current specifications.

Implementations

There are many implementations of the core XMPP specifications. See the following pages for details:

Clients

Servers

Code Libraries

Jingle

In essence, Jingle provides a way for Jabber clients to set up, manage, and tear down multimedia sessions. Such sessions can support a wide range of application types (such as voice chat, video chat, and file transfer) and use a wide range of media transport methods (such as TCP, UDP, RTP, or even in-band XMPP itself). The signalling to establish a Jingle session is sent over XMPP, and typically the media is sent directly peer-to-peer or through a media relay. Jingle provides a pluggable framework for both application types and media transports; in the case of voice and video chat, a Jingle negotiation usually results in use of the Real-time Transport Protocol (RTP) as the media transport and thus is compatible with existing multimedia technologies such as the Session Initiation Protocol (SIP). Furthermore, the semantics of Jingle signalling was designed to be consistent with both SIP and the Session Description Protocol (SDP), thus making it straightforward to provide signalling gateways between XMPP networks and SIP networks.

Jingle is defined in a number of specifications:

XEP-0166: Jingle

XEP-0167: Jingle RTP Sessions

XEP-0176: Jingle ICE-UDP Transport Method

XEP-0177: Jingle Raw UDP Transport Method

XEP-0181: Jingle DTMF

XEP-0234: Jingle File Transfer

Note: Many of the following implementations support the older Google Talk protocol and are being upgraded to support Jingle as it is defined in the specifications; contact the project developers for details.

Coccinella

Gajim

Jitsi (formerly named SIP Communicator)

Movim

Pandion

Pidgin (formerly named Gaim)

Psi

Telepathy

Yate

Libraries

libjingle (C/C++)

Smack (Java)

Telepathy Gabble (C)

yjingle (C++)

Call Managers / VoIP Servers

Asterisk

FreeSWITCH

Multi-User-Chat (MUC)

MUC is an XMPP extension for multi-party information exchange similar to Internet Relay Chat (IRC), whereby multiple XMPP users can exchange messages in the context of a room or channel. In addition to standard chatroom features such as room topics and invitations, the protocol defines a strong room control model, including the ability to kick and ban users, to name room moderators and administrators, to require membership or passwords in order to join the room, etc. Because MUC rooms are based on XMPP, they can be used to exchange not only plaintext message bodies but a wide variety of XML payloads.

MUC is defined in one primary specification (XEP-0045) and several ancillary specifications:

XEP-0045: Multi-User Chat

XEP-0249: Direct MUC Invitations

XEP-0272: Multiparty Jingle

Servers – the following XMPP servers include built-in support for MUC:

ejabberd

Jabber XCP

M-Link

MongooseIM

Openfire

Prosody

Tigase

External Components – the following standalone components can be used with a wide variety of XMPP servers:

mu-conference

palaver

Adium

JWChat

mcabber

Pidgin

AnyEvent:XMPP (Perl)

gloox (C++)

jabber-net ()

libpurple (C)

XMPP4R (Ruby)

PubSub

PubSub is a protocol extension for generic publish-subscribe functionality, specified in XEP-0060. The protocol enables XMPP entities to create nodes (topics) at a pubsub service and publish information at those nodes; an event notification (with or without payload) is then broadcasted to all entities that have subscribed to the node. Pubsub therefore adheres to the classic Observer design pattern and can serve as the foundation for a wide variety of applications, including news feeds, content syndication, rich presence, geolocation, workflow systems, network management systems, and any other application that requires event notifications. The personal eventing protocol (PEP), specified in XEP-0163, provides a presence-aware profile of PubSub that enables every user’s JabberID to function as a virtual pubsub service for rich presence, microblogging, social networking, and real-time interactions.

PubSub is defined in several specifications:

XEP-0060: Publish-Subscribe

XEP-0163: Personal Eventing Protocol

XEP-0248: PubSub Collection Nodes

Payloads

PubSub and PEP are “payload-agnostic” — you can use them as neutral transports for a wide variety of data formats. Some of the more popular payloads are listed below, especially for rich presence related to IM users:

Activities

Atom / RSS Notifications

Avatars

Chatroom Visits

Gaming Activities

Geolocation

Moods

Music Tunes

TV/Video Activities

Website Visits

Servers – the following XMPP servers include built-in support for PubSub or PEP:

Server Components

Idavoll

3. 4 Libraries

strophe (C or JavaScript)

BOSH

BOSH is “Bidirectional-streams Over Synchronous HTTP”, a technology for two-way communication over the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP). BOSH emulates many of the transport primitives that are familiar from the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). For applications that require both “push” and “pull” communications, BOSH is significantly more bandwidth-efficient and responsive than most other bidirectional HTTP-based transport protocols and the techniques known as AJAX. BOSH achieves this efficiency and low latency by avoiding HTTP polling, yet it does so without resorting to chunked HTTP responses as is done in the technique known as Comet. To date, BOSH has been used mainly as a transport for traffic exchanged between Jabber/XMPP clients and servers (e. g., to facilitate connections from web clients and from mobile clients on intermittent networks). However, BOSH is not tied solely to XMPP and can be used for other kinds of traffic, as well.

Specifications BOSH is defined in two specifications:

XEP-0124: Bidirectional-streams Over Synchronous HTTP

XEP-0206: XMPP Over BOSH

Servers The following XMPP servers include built-in support for BOSH:

Connection Managers

The following standalone XMPP connection managers can be used with a wide variety of XMPP servers:

JabberHTTPBind

Punjab

node-xmpp-bosh

rhb

Soashable

SparkWeb

Swift

Tigase Messenger

Tigase Minichat

emite (gwt)

JSJaC (JavaScript)

Swiften (C++)

XIFF (Flash)

XMPP4GWT (gwt)

xmpp4js (JavaScript)

XMPP4R (Ruby)

XMPP Explained – Extensible Messaging & Presence Protocol

XMPP remains a critical framework for chat and messaging applications 20+ years after its launch. Here’s how it works. Today’s internet landscape is practically unrecognizable compared to the 1990s, when AOL, MSN, GeoCities, Hotmail, and other long-gone services reigned supreme. But if you look underneath modern user experiences and the compact, high-tech devices that deliver them, you might be surprised to find that some core backend functions remain relatively unchanged. One constant across all this time has been XMPP, the open protocol that came to define instant messaging standards in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

XMPP is still widely used today, powering messaging giants like WhatsApp. And even if you’re looking to build a chat app that doesn’t use XMPP, a high-level understanding of this classic protocol can help you consider architectural decisions for your project and account for all of the baseline capabilities that chat users have come to expect. Let’s take a closer look at how XMPP works and what makes it unique.

Looking for a more hands-on tutorial? Learn how to code a basic functioning chat app in minutes using our interactive chat demo→

What is the Extensible Messaging & Presence Protocol (XMPP)?

Short for Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol, XMPP is an open standard that supports near-real-time chat and instant messaging by governing the exchange of XML data over a network.

XML, or Extensible Markup Language, provides a framework for storing and organizing plain text data within documents so that the data can be easily interpreted by a wide variety of network endpoints regardless of their hardware or software configuration. XMPP allows XML data, in the form of short snippets called stanzas, to be reliably sent from one endpoint to another using the internet’s Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), passing through an intermediary server along the way.

XMPP Specifications

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) standardized XMPP in the early 2000s in a series of publications, most notably RFC 6120, RFC 6121, and RFC 7622. The newer RFC 7590 expands upon XMPP, allowing for the use of Transport Layer Security (TLS) encryption with XMPP messaging. RFC 7395 allows for the creation of WebSocket bindings for XMPP. If you need to double check specific guidelines about how to implement XMPP for your specific use case, these documents are the authoritative source.

For more detail, let’s break down the meaning of each word in the protocol’s name:

Extensible

An extensible protocol is designed to evolve, with new contributions — or extensions — contributed by the community and implemented by users as needed. Rather than repeatedly rebuilding the core of XMPP, its users and the XMPP Standards Foundation (XSF) maintain a “clean” core and continually improve and add to a long list of extensions. XMPP’s extensible nature as a living open-source project is one reason the protocol is still widely used and considered secure and efficient more than 20 years after its initial launch.

Messaging

The messaging part is relatively straightforward: XMPP allows two clients to exchange text messages in near-real-time. Unlike other web-based messaging services in which the client is constantly polling the server to check for new messages, XMPP conserves bandwidth and ensures fast, chronological message delivery using an efficient push mechanism initiated by the sending machine.

Presence

If you remember away messages from AOL Instant Messenger (AIM), you already understand the concept of presence data. In addition to exchanging messages, XMPP can communicate user state (status) information like online, offline, or online but away/inactive.

Protocol

A protocol like XMPP establishes a standard structure or methodology for doing something, so that all involved parties are on the same page. A protocol is not code or software; rather, it sets expectations and technical baselines so that various hardware and software components can interact coherently.

Primary XMPP Functions

In an instant messaging use case, XMPP and XML handle most or all of the fundamental tasks we’ve come to take for granted. These functions include:

Sending and receiving direct messages between users

Checking and communicating users’ status (presence) information

Managing contact lists and subscriptions to other users (in other words, adding friends/connections to chat with)

Blocking individual users

XMPP History & Background

XMPP emerged in 1998 as the framework behind Jabber, an open-source, decentralized instant messaging alternative to now-defunct proprietary chat services like AIM and MSN Messenger. Jabber community member Jeremie Miller is credited with developing the original protocol, and in its first few years of life, people commonly referred to XMPP as simply the “Jabber protocol. ” Because of XMPP’s flexibility as an open and extensible standard, though, it was adopted broadly outside of Jabber. When the IETF officially standardized the protocol in the early 2000s, it adopted the XMPP name, which is more technically accurate given the protocol’s nature and use cases.

How the Extensible Messaging & Presence Protocol (XMPP) Works

The following core characteristics set XMPP apart from other chat and messaging services past and present.

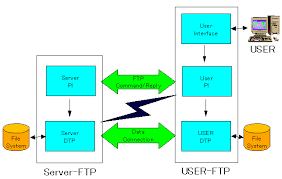

Client-Server Architecture

As mentioned above, XMPP works by passing small, structured chunks of XML data between endpoints (clients) via intermediary servers. In other words, if you send a message to your friend using XMPP, that message, as part of an XML document, first travels to a server instead of traveling directly to your friend’s device. Each client has a unique name, similar to an email address, that the server uses to identify and route messages. XMPP provides a uniform way for each client to contact the server, keeping expectations consistent between machines.

Persistent TCP Connections

Traditionally, XMPP establishes connections between client and server using the internet’s Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). These are persistent connections, so they don’t need to be reestablished each time a new message is sent. In this sense, XMPP establishes an XML stream, enveloping the free exchange or XML data between two entities. Some newer XMPP extensions use WebSockets and/or TLS encryption as well.

Asynchronous Push Messaging

XMPP lets users’ devices send messages asynchronously, meaning you can send multiple messages in a row without waiting for a response, and two users don’t have to be online at the same time in order to message each other. Messages are sent as XML stanzas — individual units of information that include the message body as well as key info like the sender’s unique ID, the recipient’s unique ID, and other metadata.

In many other client-server systems, the client (user device) repeatedly pings the server to ask if there’s any new information (messages) to download. This process, known as polling, happens on a timed interval — say, every 30 seconds — so it doesn’t offer the “instant” experience of near-real-time communication. It can also use up extra bandwidth. XMPP messaging works the opposite way: Instead of the client pulling data from the server, it pushes any new message from a user to the server, and then from the server to the recipient’s device.

Decentralized Hosting

XMPP is decentralized, meaning that anyone can spin up, maintain, and operate their own XMPP server either on-premises or in the cloud — there’s no “official” XMPP server out there somewhere. In this way, XMPP is similar to email. A proprietary service like Gmail will have its own centralized servers, but anyone who wants to create their own email system is free to do so using the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), which is similar to XMPP (but used for email).

Gateways to Other Chat/Messaging Protocols

Another powerful feature of XMPP is its ability to interact with other protocols, connecting to networks beyond where the original message originated. For example, an XMPP network could have gateways to a Short Message Service (SMS) domain to relay messages to mobile phones, to an SMTP domain to deliver aggregated messages via email, or to a different instant messaging protocol like Internet Relay Chat (IRC).

Benefits of XMPP for Chat & Messaging

As a widely adopted open protocol standardized by the IETF, XMPP has been proven reliable and adaptable by a huge community of users over more than two decades. Its extensible nature makes it an ideal intermediary between less flexible protocols, and it’s now implemented for a variety of use cases beyond peer-to-peer messaging (more on that below). Here’s more on the benefits of XMPP:

Stability & Reliability

With thousands of XMPP servers online, hundreds of developers working with XMPP, and millions of end users supported, the core protocol and its more fundamental extensions have been proven to withstand the tests of time and stress.

Want to learn more about what it takes to make an app scalable and reliable? Check out our engineering team articles on scalability.

Trustworthy Delivery

The classic Two Generals Problem explains how, in a situation where two endpoints send each other messages that must travel through unreliable territory (in this case, a network or the internet), no number of confirmation messages can ever give each endpoint total confidence that each message sent has been received. But by establishing a persistent connection over TCP, XMPP mitigates this uncertainty to a degree. When an XML stanza arrives, the recipient can be reasonably sure that any preceding stanzas in the continuous stream have been pushed along to arrive with it.

Support for Many Languages

Broad adoption and a long lifespan have also resulted in a wide range of XMPP libraries and supported languages, so developers are likely to find a match for their environment and expertise. XMPP libraries exist for languages including C, C++, C#, Ruby, Java, Python, Perl, and others.

Open Source Flexibility

As an open protocol, XMPP decentralizes development and allows for many different types of implementations that can be easily connected with each other. Anyone can build their own client, server, and library setup and distribute it as a free or paid solution.

The Future of XMPP: Beyond Traditional Messaging

As mentioned above, XMPP has been proven reliable for a number of types of communication outside of the traditional peer-to-peer messaging and presence use case. The framework can support multi-user team chat applications, and even transmission of non-text data like audio, video, and images. Some VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol) phone systems use XMPP, along with internet of things (IoT) devices like smart appliances and smart home fixtures that require machine-to-machine communication to function. Certain types of computerized industrial manufacturing equipment also use XMPP for communication.

The XSF is working to develop extensions that will support true end-to-end encryption, as well as better adaptations to accommodate sensor and actuator devices in machine communication use cases. And while some developers imagine replacing XMPP with Representational State Transfer (ReST) and JSON for many use cases, the sheer volume of existing XMPP implementations and users ensures that the protocol will be around for the foreseeable future.

Additional Resources on Chat & Messaging Infrastructure

When it comes to developing modern messaging platforms and in-app chat functionality, XMPP is just one option available to engineering and product teams. It’s worth familiarizing yourself with a variety of protocols and approaches so you can choose the path that will be most efficient and effective for your specific use case and requirements. For example, a multimedia live streaming app with real-time chat will require different tools and a different approach than a live chat solution designed for sales or customer support.

But that doesn’t mean everyone on your team has to be a chat development expert in order to ship a great product. Modern developer tools make it easy and cost effective to build custom chat and messaging functions on top of a reliable, enterprise-grade foundation instead of reinventing the wheel. Ready to start tinkering? You can build out the framework for your own chat app in minutes with a free Stream Chat trial and our library of technical tutorials.

Frequently Asked Questions about xmpp-server

What is a XMPP server?

XMPP is the Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol, a set of open technologies for instant messaging, presence, multi-party chat, voice and video calls, collaboration, lightweight middleware, content syndication, and generalized routing of XML data.

How does XMPP server work?

As mentioned above, XMPP works by passing small, structured chunks of XML data between endpoints (clients) via intermediary servers. In other words, if you send a message to your friend using XMPP, that message, as part of an XML document, first travels to a server instead of traveling directly to your friend’s device.

What is the best XMPP server?

My Top XMPP server software Ejabberd (61.6279%) Prosody (17.0543%) OpenFire (7.36434%)Aug 6, 2017