How To Read Http Headers

How to view HTTP headers in Google Chrome? – Mkyong.com

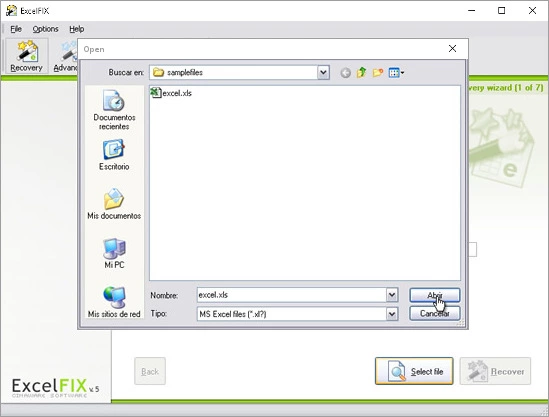

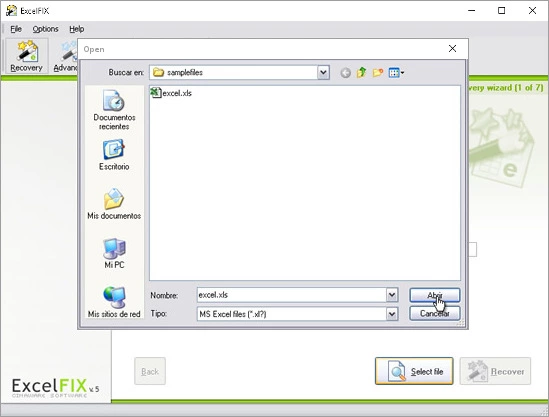

Java 17 (LTS)Java 16Java 15Java 14Java 13Java 12Java 11 (LTS)Java 8 (LTS)Java IO / NIOJava JDBCJava JSONJava CSVJava XMLSpring BootJUnit 5MavenMisc By mkyong | Last updated: January 21, 2016Viewed: 458, 868 (+2, 019 pv/w)To view the request or response HTTP headers in Google Chrome, take the following steps:In Chrome, visit a URL, right click, select Inspect to open the developer Network the page, select any HTTP request on the left panel, and the HTTP headers will be displayed on the right panel. Comments Inline FeedbacksView all commentsNot seeing what you expect? Make sure the filters are set to “All” to the right of the to the “Hide Data URLs” check box. Reply to Mark Deazley Thanks Mark. Reply to Mark Deazley You sir, you are my hero! This post is so useful, thanks! where can you see the version though? Thanx for sharing this infoAnd where the heck is the version? how to see the duration of persistant connection?? Daniel Villela 10 months agoThanksss, simple and practical Nam Nguyen H. 10 months agoDid API of every platform(Instagram, Discord, …) come from here? Thanks. It worked for this is very useful information, thanks for sharing this information with us. google extensions are very useful I also read an article on but the information which is mentioned in this article is not proper don’t go, do you know what does mean the double dots before parameter? For example:Request Headers:authority::method: GET:path: /api/data/v9. 0/$metadata:scheme: I do not know what does mean the “:”

HTTP Headers for Dummies – Tuts+ Code

Read Time:21 minsLanguages:

Whether you’re a programmer or not, you have seen it everywhere on the web. Even your first Hello World PHP script sent HTTP headers without you realizing it. In this article, we are going to learn about the basics of HTTP headers and how we can use them in our web applications.

What Are HTTP Headers?

HTTP stands for “Hypertext Transfer Protocol”. The entire World Wide Web uses this protocol. It was established in the early 1990s. Almost everything you see in your browser is transmitted to your computer over HTTP. For example, when you opened this article page, your browser probably sent over 40 HTTP requests and received HTTP responses for each.

HTTP headers are the core part of these HTTP requests and responses, and they carry information about the client browser, the requested page, the server, and more.

Example

When you type a URL in your address bar, your browser sends an HTTP request, and it may look like this:

GET /tutorials/other/top-20-mysql-best-practices/ HTTP/1. 1

Host:

User-Agent: Mozilla/5. 0 (Windows; U; Windows NT 6. 1; en-US; rv:1. 9. 1. 5) Gecko/20091102 Firefox/3. 5. 5 ( CLR 3. 30729)

Accept: text/html, application/xhtml+xml, application/xml;q=0. 9, */*;q=0. 8

Accept-Language: en-us, en;q=0. 5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Accept-Charset: ISO-8859-1, utf-8;q=0. 7, *;q=0. 7

Keep-Alive: 300

Connection: keep-alive

Cookie: PHPSESSID=r2t5uvjq435r4q7ib3vtdjq120

Pragma: no-cache

Cache-Control: no-cache

The first line is the “Request Line”, which contains some basic information on the request. And the rest are the HTTP headers.

After that request, your browser receives an HTTP response that may look like this:

HTTP/1. x 200 OK

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Date: Sat, 28 Nov 2009 04:36:25 GMT

Server: LiteSpeed

Connection: close

X-Powered-By: W3 Total Cache/0. 8

Pragma: public

Expires: Sat, 28 Nov 2009 05:36:25 GMT

Etag: “pub1259380237;gz”

Cache-Control: max-age=3600, public

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

Last-Modified: Sat, 28 Nov 2009 03:50:37 GMT

X-Pingback: Content-Encoding: gzip

Vary: Accept-Encoding, Cookie, User-Agent

The first line is the “Status Line”, followed by “HTTP Headers”, until the blank line. After that, the “content” starts (in this case, the HTML output).

When you look at the source code of a web page in your browser, you will only see the HTML portion and not the HTTP headers, even though they actually have been transmitted together, as you can see above.

These HTTP requests are also sent and received for other things, such as images, CSS files, JavaScript files, etc. That’s why I said earlier that your browser sent at least 40 or more HTTP requests as you loaded just this article page.

Now, let’s start reviewing the structure in more detail.

How to See HTTP Headers

I used Firefox Firebug to analyze HTTP headers, but you can use the Developer Tools in Firefox, Chrome, or any modern web browser to view HTTP headers.

In PHP:

getallheaders() gets the request headers. You can also use the $_SERVER array.

headers_list() gets the response headers.

Further in the article, we will see some code examples in PHP.

HTTP Request Structure

The first line of the HTTP request is called the request line and consists of three parts:

The “method” indicates what kind of request this is. The most common methods are GET, POST, and HEAD.

The “path” is generally the part of the URL that comes after the host (domain). For example, when requesting “, the path portion is “/tutorials/top-20-mysql-best-practices–net-7855”.

The protocol part contains HTTP and the version, which is usually 1. 1 in modern browsers.

The remainder of the request contains HTTP headers as Name: Value pairs on each line. These contain various information about the HTTP request and your browser. For example, the User-Agent line provides information on the browser version and the Operating System you are using. Accept-Encoding tells the server if your browser can accept compressed output like gzip.

You may have noticed that the cookie data is also transmitted inside an HTTP header. And if there was a referring URL, that would have been in the header too.

Most of these headers are optional. This HTTP request could have been as small as this:

And you would still get a valid response from the web server.

Request Methods

The three most commonly used request methods are GET, POST, and HEAD. You’re probably already familiar with the first two from writing HTML forms.

GET: Retrieve a Document

This is the main method used for retrieving HTML, images, JavaScript, CSS, etc. Most data that loads in your browser was requested using this method.

For example, when loading an Envato Tuts+ article, the very first line of the HTTP request looks like so:

GET /tutorials/other/top-20-mysql-best-practices/ HTTP/1. 1…

Once the HTML loads, the browser will start sending GET requests for images that may look like this:

GET /wp-content/themes/tuts_theme/images/ HTTP/1. 1…

Web forms can be set to use the GET method. Here’s an example.

When that form is submitted, the HTTP request begins like this:

GET / HTTP/1. 1…

You can see that each form input was added to the query string.

POST: Send Data to the Server

Even though you can send data to the server using GET and the query string, in many cases POST will be preferable. Sending large amounts of data using GET is not practical and has limitations.

POST requests are most commonly sent by web forms. Let’s change the previous form example to a POST method.